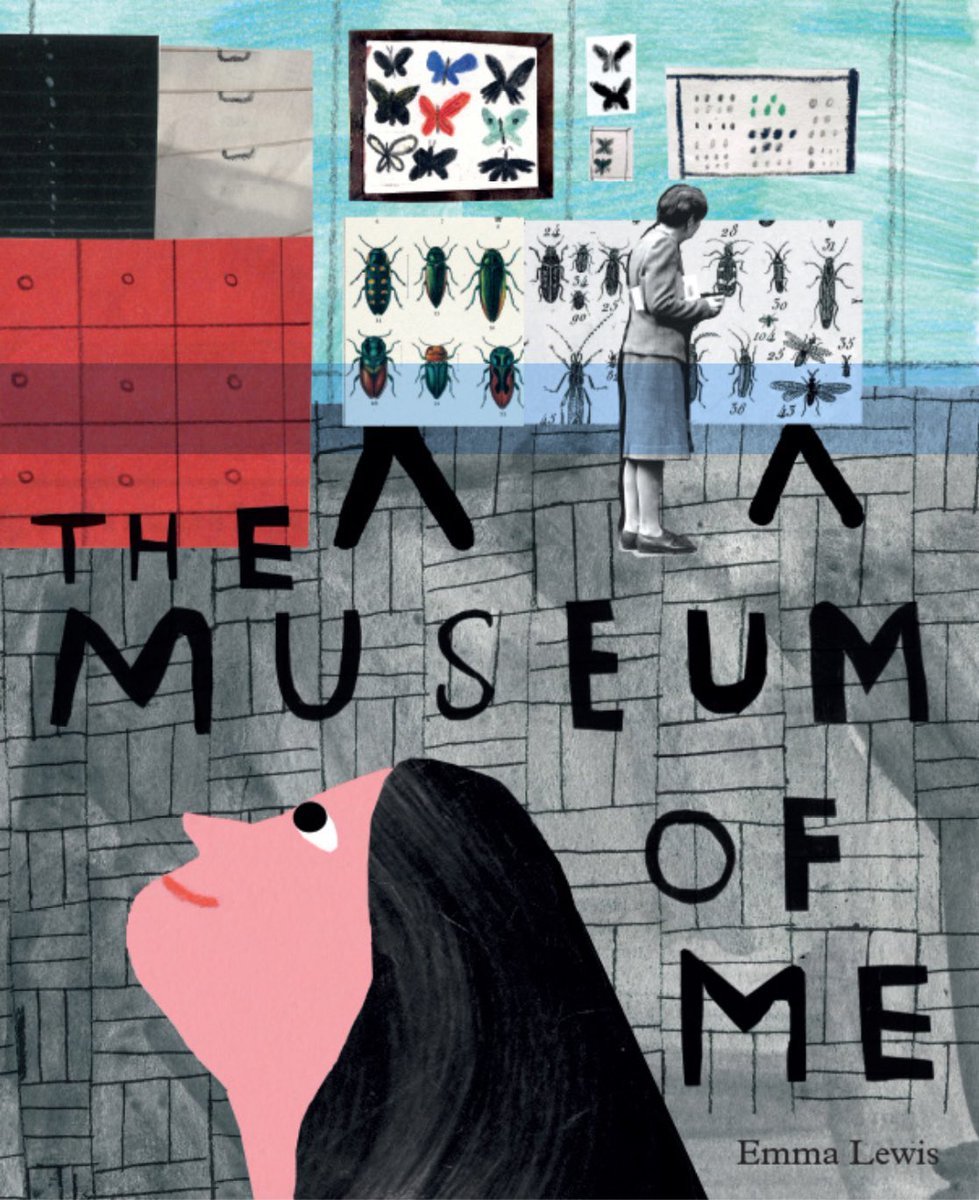

Author: Emma Lewis

Illustrator: Emma Lewis

Year: 2016

Publisher: Tate

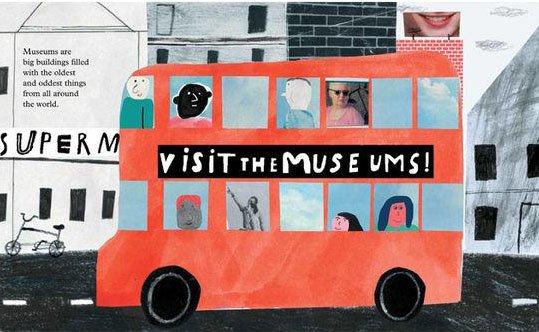

The Museum of Me by British artist Emma Lewis — winner of the 2017 Bologna Ragazzi Opera Prima Award — offers an unusually sincere, child-eye view of what a museum is and why it exists in the first place.

The Museum of Me by British artist Emma Lewis — winner of the 2017 Bologna Ragazzi Opera Prima Award — offers an unusually sincere, child-eye view of what a museum is and why it exists in the first place.

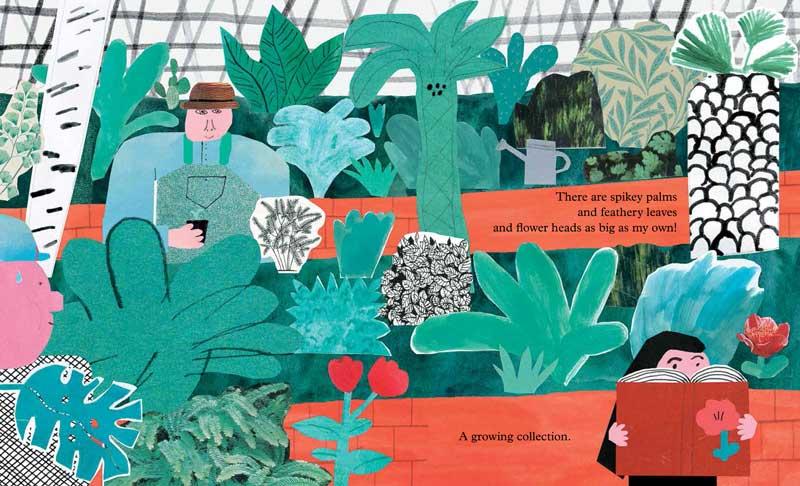

A little girl wanders through all kinds of galleries (there’s even a botanical garden), studying the exhibits and trying to understand how and why these objects ended up here. What do they say about the people who once owned them, or about the ones who created them?

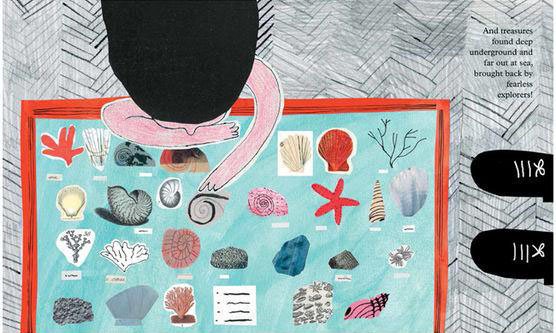

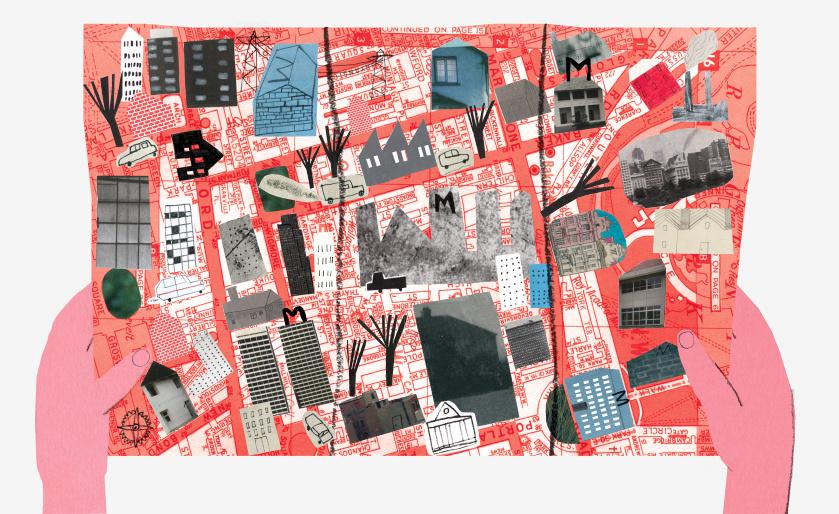

Every object was once important to someone — or maybe not important at all, and that someone didn’t even notice when they lost it. And now, centuries later, we look at it behind glass without thinking that we, too, are owners of our own artifacts that might one day end up in a museum. After all, we also might have a box of “treasures” under the bed: old books, photos, scraps of fabric, toys. A collection that is no less — and perhaps even more — important to us. That’s why the center of each spread isn’t the exhibits themselves but the heroine and other visitors, who matter just as much as the Venus de Milo.

Pinned insects, ancient amphorae, rare palms, terracotta figurines — they’re not only entry points into science but also invitations to listen to your own associations, to “claim” these museum pieces in a small way. You remember a similar beetle crawling up the wall at your grandmother’s house; a clay dog almost identical to the one at home on your shelf; a Neanderthal figure that looks suspiciously like your neighbor across the hall. There could be countless examples, and all of them help shift our relationship with museums: away from the idea of a distant scientific temple and toward a starting point for our own collections and treasure hunts — a place where glass cases inspire rather than bore.

What do our things say about us? What do our rooms or our clothes reveal? Which five or ten objects would make it into the first exhibition of your own Museum of Me?

This book is a little museum in itself — built from many small fragments. Cutouts from colored paper, old photographs, magazines, and newspapers rest on grid-lined notebook pages, watercolor washes, or pencil-drawn museum halls. The technique reinforces the sense of a curated collage, the orderly chaos that exists in every museum. And the only thing that can truly tie it all together is our own feelings and thoughts.