The outstanding American artist Dahlov Ipcar described her style as “non-intellectual cubism” and became known worldwide for her original and unusual works. Her paintings hang in dozens of American galleries, schools, and libraries, as well as in the Whitney and Metropolitan museums. Dahlov Ipcar was a true workaholic: she painted every day until the very last day of her life, and even after losing much of her eyesight by the age of ninety, she did not stop working.

Dalov Ipkar at the age of 90

Dalov Ipkar at the age of 90

Ipcar’s style is captivating and inspiring, her works invite long, attentive looking. The highest task of any artist is to develop a unique way of seeing, to create something new and unlike anything else. How this vision formed in Dahlov can be understood, at least in part, from her autobiographical essay “My Family, My Life, My Art”, published in 2002.

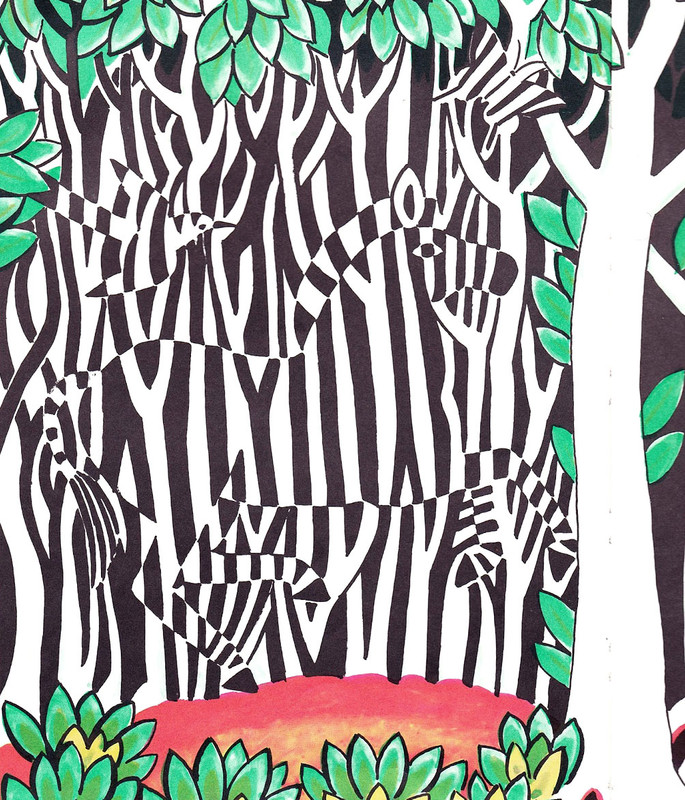

Illustration from the book “Black and White” (Knopf, 1963)

Illustration from the book “Black and White” (Knopf, 1963)

Dahlov Ipcar was born in 1917 in Vermont, into a family of highly diverse artists. She grew up in New York City, in a home filled with a natural atmosphere of creativity that shaped much of her future. Her father, William Zorach, an immigrant from Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire), painted and sculpted; her mother, Marguerite, worked in the applied arts. Most of the objects in their home were made or decorated by hand, and the house was filled with paintings and sculptures—many of which were, for the young girl, almost like members of the family.

In Dahlov’s early childhood, her father worked at home, which allowed her to watch the entire process of creating a sculpture; her mother also worked on her art there. On one of the walls she painted large figures of Adam and Eve with the tempting serpent in the Garden of Eden, and the whole house was decorated with her handmade batiks and rugs. Marguerite embroidered the family’s clothing so brightly and vividly that she was once called to the school and scolded for the appearance of her children. She replied that she could not afford to buy ordinary clothes, but if she made something by hand, it ought to look magnificent. And indeed, it looked magnificent — and very exotic. In her youth, while traveling in India, Marguerite, overlooking the poverty around her, became deeply taken with the country’s vivid beauty and unusual colors, and expressed them fully in her work. Both she and her husband were inspired by the idea of an idealistic pastoral world where people wear colorful clothes — or wear none at all.

Illustration from the book “Lost and Found” (Doubleday, 1981)

Illustration from the book “Lost and Found” (Doubleday, 1981)

Dahlov’s parents met in Paris in the early 1900s, enthusiastically embraced the “virus” of the new art doctrine, and stood at the forefront of modern American art of the time. But gradually their life turned into a struggle. Their works sold increasingly poorly, and the family lived in poverty. To pay for Dahlov and her older brother Tessim to attend a prestigious school with a progressive, child-centered teaching approach, William Zorach took a job there as an art teacher. Constantly burdened by lack of money, Tessim gave up the idea of becoming an artist forever, despite his considerable talent for drawing. Dahlov, however, barely noticed the poverty.

At school, any form of creativity was encouraged. Dahlov most enjoyed drawing and clay modeling; she also happily wrote poems and stories. A devoted animal lover, she had dreamed of having her own farm since the age of three. “I tell parents: never underestimate how early a child’s life plan is made.”

Illustration from the book “Hard Scrabble Harvest” (Doubleday, 1976)

Illustration from the book “Hard Scrabble Harvest” (Doubleday, 1976)

Her parents decided not to give Dahlov formal art instruction, letting her “reinvent the wheel” and strengthen her basic artistic skills on her own. At school she learned about techniques and new materials, but composition, color harmony, design, and form she explored independently. From an early age she was often taken to museums, most frequently to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where she was deeply impressed by the paintings on Egyptian tombs, Greek vases, Renaissance chests, and Indian miniatures. Even as a child she learned to see the shared features in these seemingly very different works of art from various cultures and eras: simple forms, color play, and careful attention to detail. She tried to memorize what she saw and later worked from memory, making no sketches from life. “Where my memory failed,” she later recalled, “my imagination stepped in.”

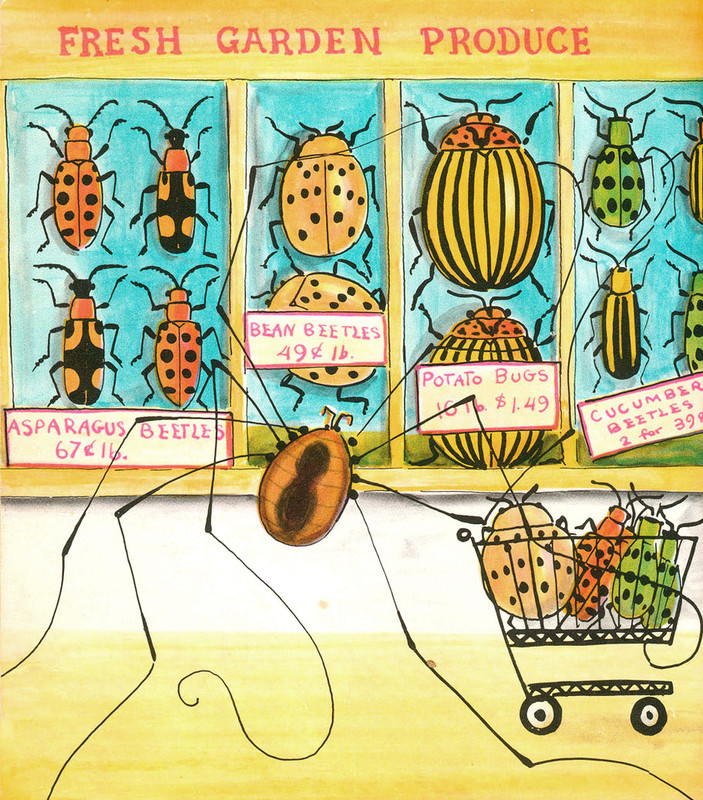

Illustration from the book “Bug City” (Holiday House, 1975)

Illustration from the book “Bug City” (Holiday House, 1975)

In 1923, her parents bought a farm in Maine. Marguerite furnished it with antique furniture and decorated the living room with her own mural of leaves, animals, and nude figures. Outside, the house was surrounded by flowers, and there was a vegetable garden. The 28 acres of fields and forests later expanded by an additional 65 acres from a neighboring farm. This farm became Dahlov’s main home for her entire life. It was located on the ocean, where the children fished and set traps for lobsters. Gradually, her parents acquired livestock: first a cow so the children would always have fresh milk, then a horse to help gather hay for the cow, another cow just in case, and a riding horse for Dahlov — eventually, a worker was hired to assist with the growing farm. All the farm work was done by the children together with their parents, and these skills, according to Dahlov, proved very useful later in her life.

Dahlov continued her education in New York; she attended two of the most progressive schools of the time — Walden and Lincoln — both of which had strong art departments. “Nevertheless, the art ideas of the teachers did not impress me much, I had plenty of my own. Fortunately, no one stopped me from putting them into practice.” Dahlov became interested in the ideas of Mexican artists and muralists Diego Rivera and José Orozco; she liked simple forms. In her final year at Lincoln, she tried working on large formats for the first time, depicting workers and soldiers of the First World War.

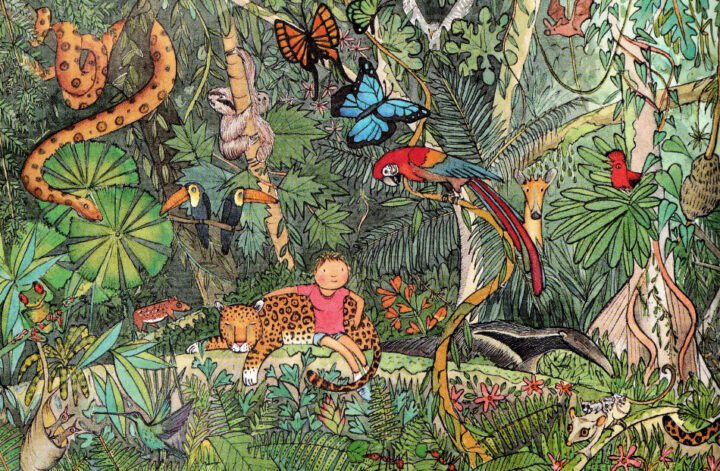

Illustration from the book “A Flood of Creatures” (Gannett Books, 1985)

Illustration from the book “A Flood of Creatures” (Gannett Books, 1985)

At sixteen, Dahlov received a scholarship to Oberlin College in Ohio, but the strict academic environment, outdated teaching methods, and blind adherence to drawing traditions quickly disappointed her. She refused to continue her formal studies and devoted herself entirely to working in her studio. Two years later, she married Adolf Ipcar, her math tutor, and moved with him to a farm. They lived modestly, but they could afford an easel for Dahlov. In 1939, two of her works were exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, and later that year her first solo exhibition, Creative Growth, was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition included works from her early years up to age 21. The organizer, Victor D’Amico, intended to show how an ordinary child, with constant creative support, could grow into a true artist. Dahlov was unable to attend the opening because she was giving birth to her first child at that time.

Illustration from the book “Wild And Tame Animals” (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

Illustration from the book “Wild And Tame Animals” (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

The farm soon ceased to be the family’s main source of income. In 1937, Dahlov Ipcar won two competitions to create her own murals, and by completing the commissions, she earned more than a thousand dollars — a huge sum at the time; for comparison, a new Buick cost around $500. However, starting in 1945, her main source of income became illustrations for children’s books.

Illustration from the book “Wild And Tame Animals” (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

Illustration from the book “Wild And Tame Animals” (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

“My father always told me, “Never do art with the idea of selling it. Do the best work you can. Do it to please yourself. And then try to sell it.” In 1945, Dahlov Ipcar illustrated her first children’s book, The Little Fisherman by Margaret Wise Brown. She enjoyed this work so much that she began creating her own books. One of them, One Horse Farm, was reprinted for thirty years. After its publication, Ipcar received a check for a remarkable $2,000 — an enormous sum at that time. Dahlov recalled that nearly all of her projects were successful. In total, she wrote and illustrated 30 children’s books, 4 novels for adolescents, and one collection of stories for adult readers.

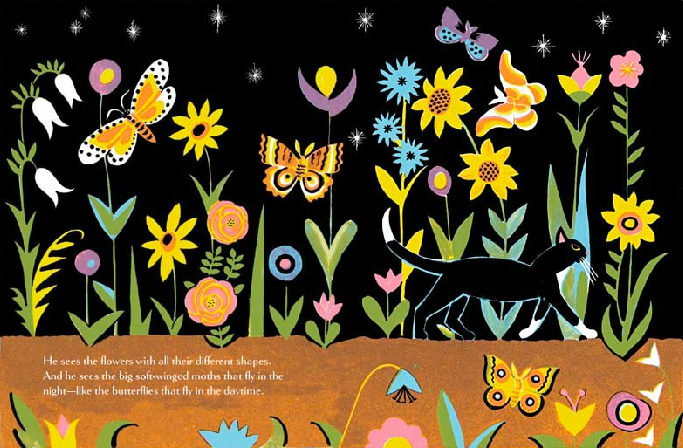

Illustration from The Cat at Night (Doubleday, 1969)

Illustration from The Cat at Night (Doubleday, 1969)

Dahlov never stopped painting. “On a farm, you get up at five in the morning — you can get a lot done.” She never faced a choice between art and family; caring for her two sons — Robert William (1939) and Charles (1942) — was harmoniously combined with her painting. “My children were a joy to me, and there was no problem working with them around — I just let them play at my feet as I painted. They would even run toy fire engines up and down my easel, but it didn’t bother me. The only problem was how to keep them safe when we were doing field work, such as plowing with the horse. Once on a TV interview I was asked about this and I said, “Oh, we just tied them to a tree.” When I listened to the program later, I was horrified. The picture that popped into my mind (and, no doubt, into the minds of the viewers) was of two small prisoners bound hand and foot to the stake like Joan of Arc. Of course, it wasn’t anything like that. In those days, it was common to tether small children to keep them out of harm’s way. It probably just sounds worse to say we always gave them plenty of rope.” The children grew up helping their parents in the fields and around the farm. Dahlov regretted that they did not receive the same modern education she had; the farm itself became the school for her sons and was a central theme in her work during the 1940s and 1950s. Friends often visited the farm, including artists Thomas Hart Benton and Waldo Peirce. Around the same time, Dahlov became interested in the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his series of paintings depicting the seasons.

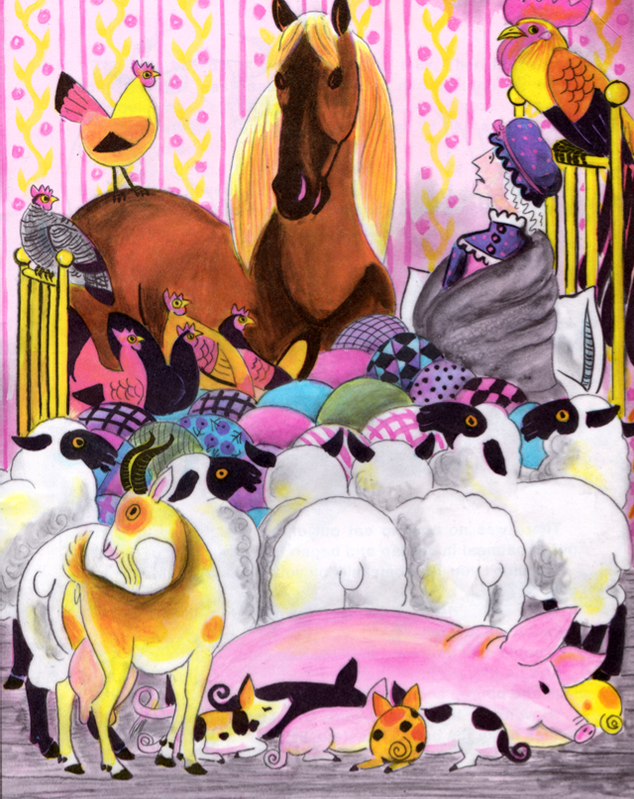

Illustration from the book “One Horse Farm” (Doubleday, 1950)

Illustration from the book “One Horse Farm” (Doubleday, 1950)

Dahlov wrote somewhat shyly that her style was often classified as social realism; in reality, she never attempted to put any social or political meaning into her work. The style she chose was primarily a suitable means of visual storytelling; in this sense, social realism for Dahlov was similar to the Victorian style — in both, visual art was the most important language of narrative.

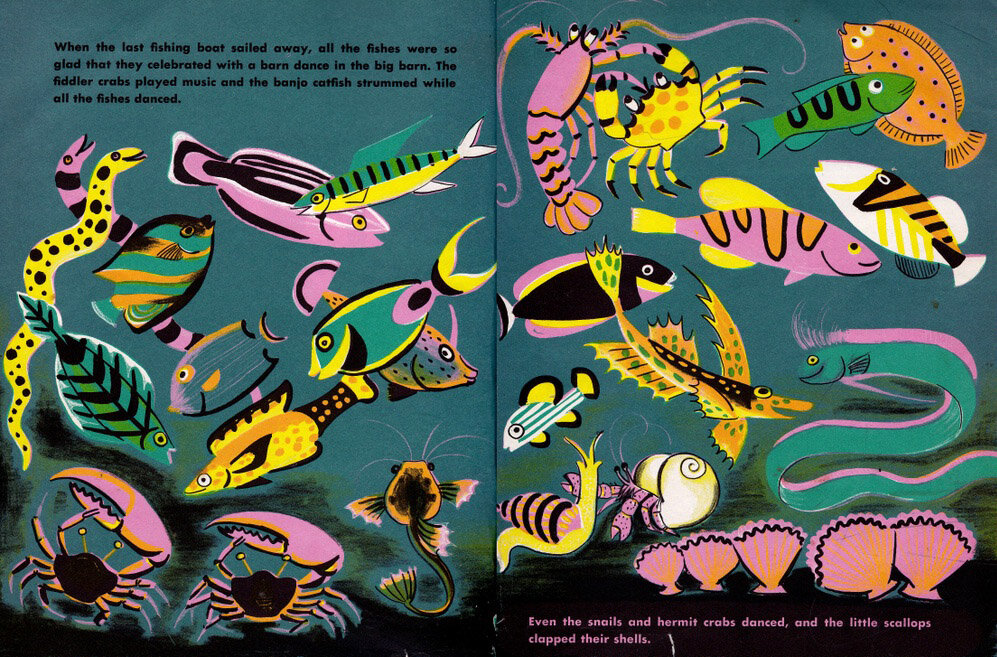

Illustration from the book “Deep Sea Farmer” (Alfred A. Knopf, 1961)

Illustration from the book “Deep Sea Farmer” (Alfred A. Knopf, 1961)

In her autobiography, Dahlov admitted that when she conceived a new book, she would first draw the illustrations and then write the story to accompany them, emphasizing her indifference to the commercial aspect of illustrating — she created her books based solely on her own wishes, with minimal interference from publishers. The main criterion in her work was always a sense of responsibility toward her young readers. “I am convinced that a child who grows up without access to art is like a child who grows up without love; and the most accessible art for them is children’s books.”

Illustration from the book “The Wonderful Egg” (Doubleday, 1958)

Illustration from the book “The Wonderful Egg” (Doubleday, 1958)

In the 1950s, when Dahlov Ipcar’s paintings had just begun to sell, the era of Abstract Expressionism emerged in art. The trendy art did not appeal to Dahlov. “I have always liked Cubism, I liked Picasso and Braque; Abstract Expressionism can be very emotional and expressive, but it lacks form, and my soul cannot do without clear boundaries.”

Illustration from the book “The Wonderful Egg” (Doubleday, 1958)

Illustration from the book “The Wonderful Egg” (Doubleday, 1958)

“Art is like a maze. You have to stop occasionally and reconsider where you are going and why. When I begin to feel that I have been going in the wrong direction or that I have reached a dead end, I will try something different. I feel it has all been a steady process of finding the art form that gives me the fullest personal satisfaction. If you count my childhood art, I have gone through at least four major changes in my style — not following any fashion, but because of some inner need.”

Illustration from the book “I Like Animals” (Knopf, 1960)

Illustration from the book “I Like Animals” (Knopf, 1960)

In her continuous creative journey, the artist worked in a wide range of techniques, using various methods and tools. For example, she is considered the originator of the phenomenon known as “soft sculpture.” It all began with toy animals for children, for which she used bright printed fabrics. Their first exhibition took place in 1956.

The idea arose to create illustrations for one of her books in the form of fabric collages, but printing such illustrations proved too expensive; so Dahlov made imitations of printed fabrics using watercolor. This is how the patterns came about. They became a new stylistic element for Ipcar. Odalisque (1960) was the first experiment using them.

In Dahlov’s art, bright, expressive, and very original, a thread of her lifelong love for animals runs clearly. She sketched them from early childhood, and it did not bother her at all that she did not have the opportunity to see many of them in real life — her family did not travel outside the United States. As a child, Dahlov often visited the zoo and the Museum of Natural History. She described her method of depiction as follows: “… I did need to do some research, for the animals and fishes were all new to me. But still I tried to transform them, to make them my own. I do not make numerous plans or drawings before starting a painting. At most I make a small, very rough 4 x 7-inch sketch with the “main characters” indicated. All final drawing is done very freely with the brush directly on the canvas. The result is spontaneous and fresh, not “worked over.”

Illustration from the book “I Like Animals” (Knopf, 1960)

Illustration from the book “I Like Animals” (Knopf, 1960)

The Ipcar family always led an active public life, participating in numerous “green” environmental initiatives. Her sons traveled all over the world. Dahlov was happy all her life with her husband and never doubted that she had made the right choice in refusing a “career as a New York celebrity” and instead preferring life on the farm, fully dedicating herself to her art and beloved family.

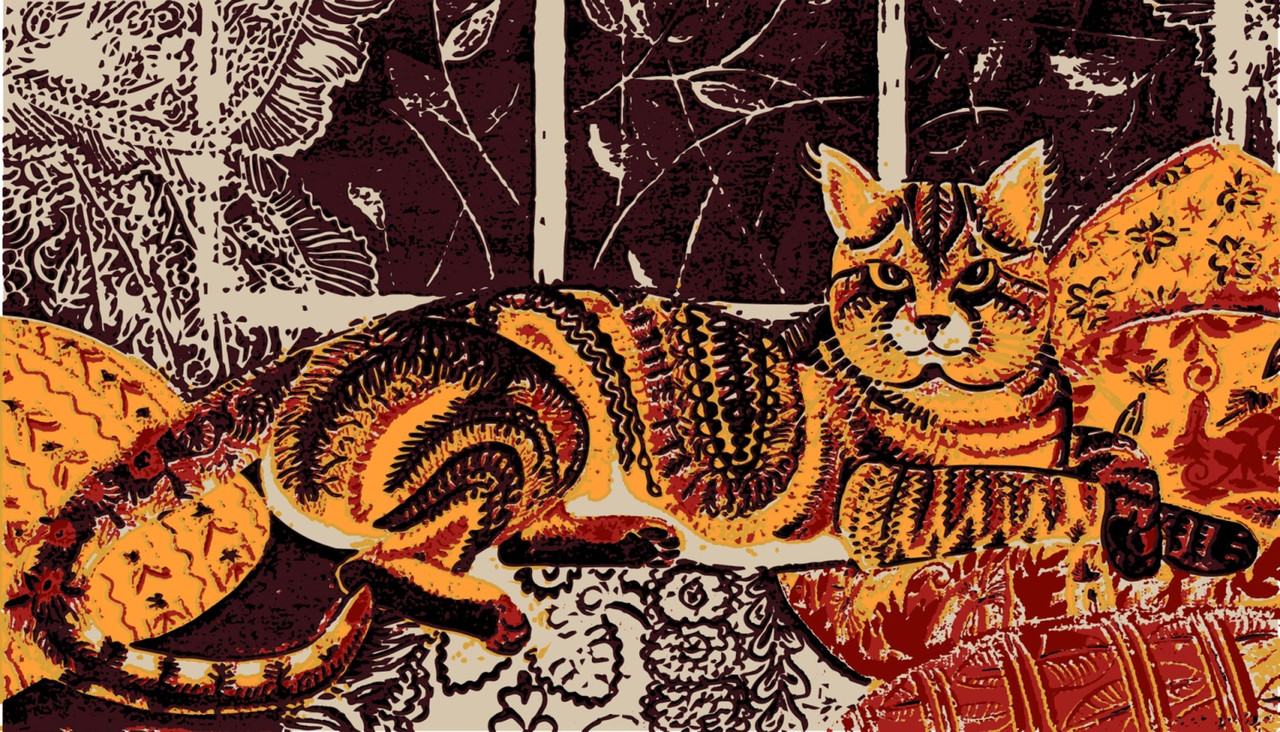

Illustration from the book “Black and White” (Knopf, 1963)

Illustration from the book “Black and White” (Knopf, 1963)