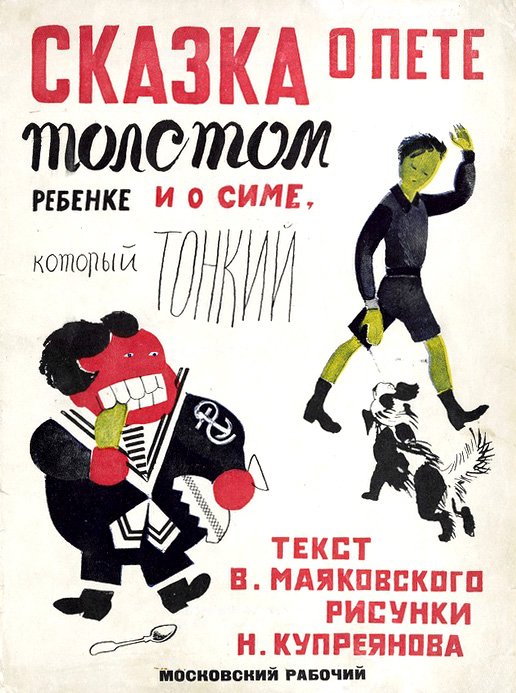

Author: Vladimir Mayakovsky

Illustrator: Nikolai Kupreyanov

Year: 1925

Publisher: Moskovsky Rabochy

“The Tale of Petya, the Fat Child, and Sima, the Thin One” was published by Moskovsky Rabochy in 1925 and became Vladimir Mayakovsky’s first children’s book.

“The Tale of Petya, the Fat Child, and Sima, the Thin One” was published by Moskovsky Rabochy in 1925 and became Vladimir Mayakovsky’s first children’s book.

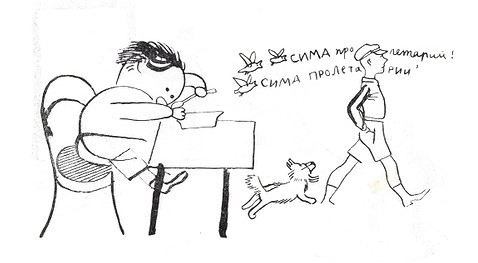

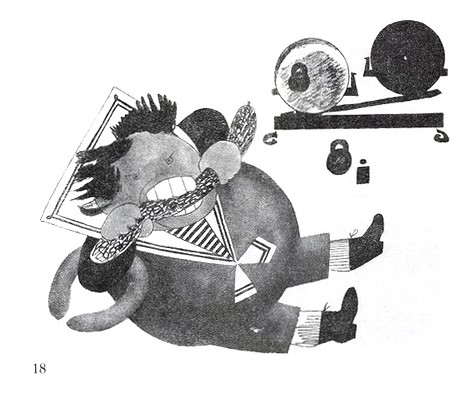

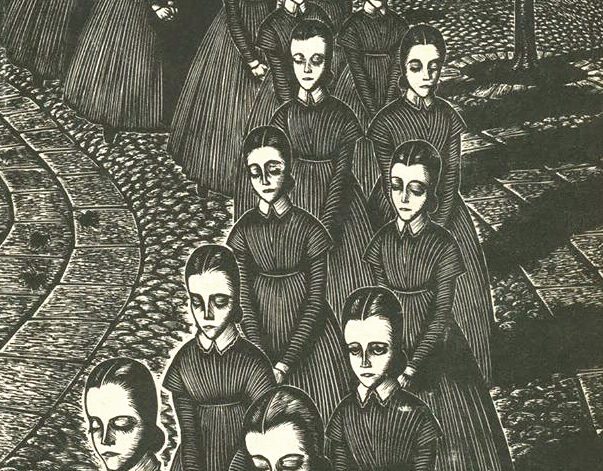

The poem tells the story of Petya, the repulsive son of a bourgeois, and Sima, the virtuous child of a proletarian blacksmith. It spans fourteen spreads, each accompanied by an illustration. Kupreyanov’s drawings for Mayakovsky’s tale were described by some critics as a “rally in verse.” The images are concise and echo the traditions of poster art—especially evident on the cover—yet rich in everyday details, making them exceptionally expressive. Kupreyanov fully revealed his mastery as a graphic artist and again demonstrated his skillful use of grayscale: only three of the illustrations are in color.

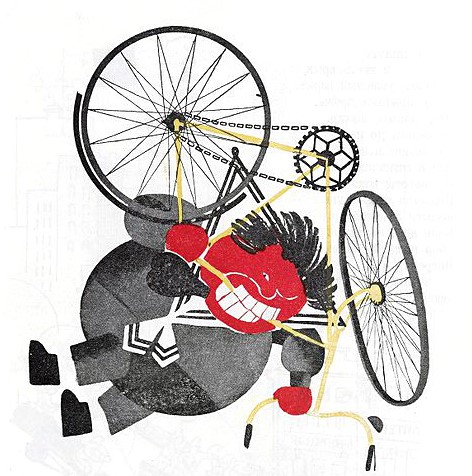

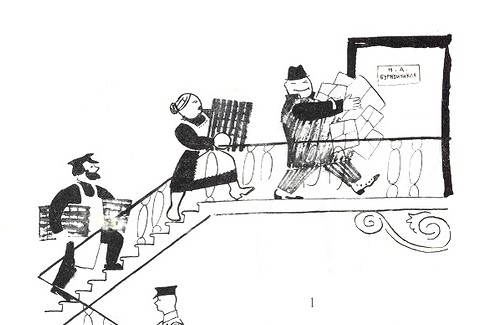

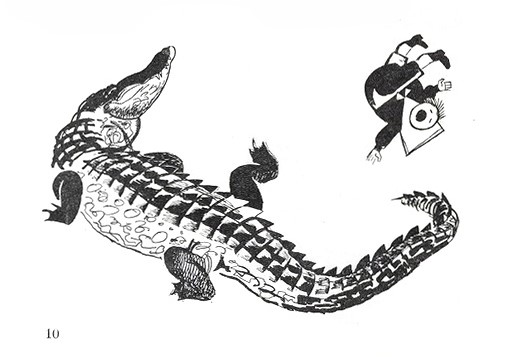

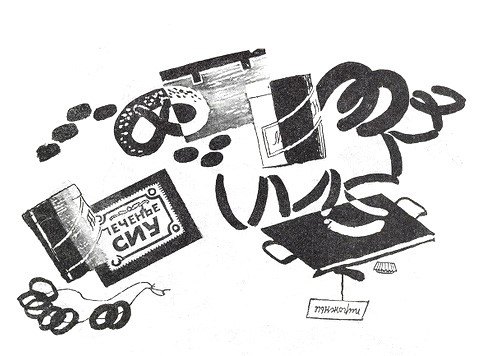

Color is used deliberately—to highlight the introduction of key characters (Petya and Sima appear in color on the cover, and the blacksmith is shown on a separate page against bright red factory buildings) and to emphasize the climactic scene, where Petya fails to chew a bicycle tire and bursts in two. The grotesque tone of the text is matched by equally exaggerated illustrations: unlike the other characters—the blacksmith or the postman—Petya barely resembles a human being, with a caricatured face and an oversized jaw. Kupreyanov skillfully blends simplified realistic depictions of apartments, cities, animals, and Soviet citizens with caricature, seamlessly weaving fantasy into everyday life. He doesn’t always follow the writer’s text strictly; in some places, he adds personal touches. For instance, on the drawing with the postman carrying an envelope with Petya inside, the name of the addressee, P. Ettinger—a critic Kupreyanov corresponded with—is clearly visible. Kupreyanov also designed custom lettering for the book, which appears on the cover, in the final pages, and on some of the illustrations.

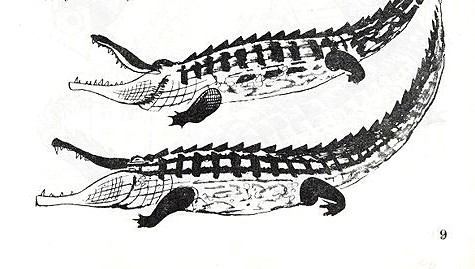

At that time, Kupreyanov was an indefatigable caricaturist, influenced by the works of George Grosz. This is clearly reflected in his drawings. Perhaps—though we cannot be sure—when depicting the crocodiles threatening bourgeois Petya, he recalled his own childhood (his uncle Mark, who lived with Kupreyanov’s grandfather, kept two crocodiles in a terrarium). The book’s release was followed by a wave of criticism: many were outraged by the fairy-tale elements in both text and illustration. For example, A. Grinberg wrote, “Isn’t this book a parody of all that literature which, under the banners of drums, sickles, hammers, pioneers, and other political emblems of children’s books, floods the Soviet market? Did Mayakovsky intend to offer readers a biting satire reflecting the childish political inventions of publishers and writers who, deep down, are alien to the new educational ideals?”

Mayakovsky never returned to writing fairy tales. Kupreyanov, however, continued illustrating for magazines such as Krokodil and Bezbozhnik, worked on children’s books, and went on numerous creative trips, including to Central Asia.